Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios fronterizos

versión On-line ISSN 2395-9134versión impresa ISSN 0187-6961

Estud. front vol.21 Mexicali 2020 Epub 15-Ene-2021

https://doi.org/10.21670/ref.2009051

Articles

Perception of poverty in the members of an emerging migratory flow. Transnational narratives between Tres Valles and Kansas

a Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, Tampico, Tamaulipas, Mexico, e-mail: alfredo.sanchez@uat.edu.mx, rcogco@hotmail.com

This article presents the result of a research on the perception of poverty in the members of an emerging transnational migratory flow (Tres Valles, Veracruz in Mexico and Kansas, United States). The study was developed with a qualitative methodological design, with the use of techniques such as documentary review, in-depth and semi-structured interviews and participant observation, between 2014 and 2016. The findings are presented from the analysis of the interviewees' narratives considering dimensions such as the conceptualization of poverty, income, comparison of poverty in the place of origin and destination, and the requirements necessary to be considered poor. One of the conclusions is that the way in which poverty is perceived is the result of the transnational migratory dynamics in which the tresvallenses have been involved.

Keywords: poverty; transnational migration; migratory flow; Veracruz; Kansas

Este artículo presenta el resultado de un trabajo de investigación sobre la percepción de pobreza en los integrantes de un flujo migratorio emergente transnacional (Tres Valles, Veracruz en México y Kansas, Estados Unidos). El estudio se desarrolló con un diseño metodológico cualitativo, con el uso de técnicas como la revisión documental, entrevistas a profundidad y semiestructuradas y observación participante, entre 2014 y 2016. Los hallazgos se presentan a partir del análisis de las narrativas de los entrevistados y la consideración de dimensiones como la conceptualización de pobreza, los ingresos, la comparación de pobreza en el lugar de origen y destino y los requerimientos necesarios para ser considerado como pobre. Una de las conclusiones es que la forma en que se percibe la pobreza es el resultado de las dinámicas migratorias transnacionales en la que se han involucrado los tresvallenses.

Palabras clave: pobreza; migración transnacional; flujo migratorio; Veracruz; Kansas

Introduction

Mexican migration to the United States is a historical phenomenon with at least five stages or phases that occurred during the 20th century. Each one of these had a duration of approximately twenty years: the recruitment stage (1900-1920), the deportations stage (1921-1939), the bracero period (1942-1964), the era of the undocumented (1965-1986) and the legalization and clandestine migration stage (1987-2001) (Durand & Massey, 2019).

At the same time, several analyses have identified another stage different from the previous ones: the new era of migrations1 (Castles et al., 2014) which, in addition to pointing out the particularities of the migratory situation between Mexico and the United States, can be applied as a focus of analysis for migratory movements around the world. This stage was proposed during the 1990s (Durand et al., 1999) and explains that migration flows have the following characteristics: accelerated processes of globalization; reconfiguration of industrial zones that attract labor─the new labor market (Phillips & Massey, 1999); increase in the “porosity” of borders; impoverishment of regions or countries that expel migrants; growing establishment of transnational relations between places of origin and destination of migrants; climate changes that encourage the mobility of people in search of alternatives for sustainability; adjustments to the migration laws of the countries involved; establishment of migration flows not only from north to south but also in a south-south direction; among other characteristics (Castles et al., 2014; Baeninger et al., 2018; Durand & Massey, 2019).

Based on the changes in migration between Mexico and the United States since the 1980s, it can be said that the migration map is in a constant state of reconfiguration, which is subject to changes in bilateral relations and, even more so, to the political adjustments and economic fluctuations that occur primarily in the United States (Facchini et al., 2015). For example, since 2008, with the economic crisis in the United States (Zurita et al., 2009), the decrease in the number of Mexican immigrants to the United States has become evident (Passel & Cohn, 2008).

At the same time, in this process of migratory reconfiguration, changes were detected in the areas of expulsion (in Mexico) and reception (in the United States) of migrants, an evolution that had already been underway since the last two decades of the 20th century (Massey, 2015). For example, the traditional states of expulsion of Mexican migrants such as Zacatecas, Michoacan, Guanajuato, and Jalisco, among others, have shown a stagnation or reduction in the number of their emigrants. In contrast, states such as Veracruz have risen to significant positions in terms of migration intensity. In addition, new Mexican migrant-receiving states have appeared in the United States, for example, Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri, among others.

On the other hand, conditions such as unemployment, poverty, marginalization, and violence have been discussed as being the main reasons why Mexicans decide to emigrate to the United States since they are motivated by economic progress and improvement in the quality of life that “awaits” them upon arrival in the United States. However, Mexican migrants also experience conditions of unemployment, precariousness, and poverty in the United States (Delgado, 2013); a situation that has worsened since the 2008 economic recession in the United States, and subsequent downturns.

According to official figures, among Hispanic migrants in the United States, Mexicans have the highest levels of poverty (Albo & Ordaz, 2011; BBVA, 2015). According to the Pew Research Center, 34.6 million people of Mexican origin were counted in the United States in 2015, of whom 26% are considered poor, a rate higher than that of the general population of the United States, which is 16%.2 Specifically, for Kansas, according to data from the American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2015),3 the population living in poverty in this state represents 13.18% (381 353 inhabitants) of the total population, of whom 20.9% are Hispanic (79 775 inhabitants), and 17.6% are Mexican (67 023 inhabitants). In other words, Mexicans represent 84% of the total number of poor Hispanics in the state. Among these poor people are migrants from the municipality of Tres Valles, Veracruz, Mexico, who have migrated to the state of Kansas, United States─although it can be said that the official figures do not specify the origin of the migrants.

These considerations were taken into account to problematize some observations and thus focus interest on the narratives of the perception of poverty of the members of an emerging flow in the United States. In order to achieve this objective, the analysis seeks to answer the following question: What narratives on the perception of poverty are configured among the members of an emerging migration flow with transnational characteristics? In order to answer this question, qualitative research was conducted between 2014 and 2016, using as a research technique the in-depth interview, semi-structured interview, and participant observation in both scenarios of the emerging migration flow between Tres Valles, a municipality in the state of Veracruz, and Johnson County in the state of Kansas, in the United States.

Therefore, this article shows the narratives that are constituted from the transnational dynamics and that are related to the perception of poverty beyond the official objective measurements.

Migratory Context: Emigration from the State of Veracruz

The emergence of the migratory dynamics of the state of Veracruz was already highlighted by some migration scholars, such as Massey and collaborators (1987), who paid particular attention to the migratory networks that were becoming stronger over the years. At first, the formation of these connections was slow. The destinations (California, Illinois, Texas, Arizona, among others) seemed to be the traditional states, but over time the receiving cities diversified, and the process became a mass phenomenon (Alarcón et al., 2014).

Between 19904 and 2000, the people of Veracruz began a search for alternatives to improve their quality of life through better jobs as a result of the dismantling of the national industry located in the state, which caused acute unemployment. As a result, during the early 1990s, the people from Veracruz migrated from the agricultural fields in the north of the country to the maquiladora centers in the border cities and, later, spread to the United States (Pérez, 2012), so that Veracruz could already be seen as the origin that would nurture new national and international migration flows.

The substantial growth of emigration in Veracruz was sustained for several years, as can be seen in Figure 1, where the departure of the people from Veracruz to the northern border and the United States between 1993 and 2016 is evident.

Source: created by the author with data from Encuesta sobre Migración en la Frontera Norte de México (EMIF NORTE) (El Colef et al., 2002-2017).

Figure 1 Veracruz migrants to the northern border and the United States, 1993-2016

Concerning the characterization of this growing emigration of people from Veracruz to the United States, about 90% are undocumented, and migrants come mostly from rural areas and the agricultural sector, although the urban population also participated in the migration flow (Binford, 2003; Garrido, 2010; Nava, 2012). Different municipalities in Veracruz supported themselves as suppliers of migrants, including Landero y Coss, Yanga, Yecuatla, Cuitláhuac, and Carrillo Puerto, as well as Tres Valles (Conapo, 2012). All these municipalities are socially deprived, and their population is in a situation of poverty or extreme poverty, according to the measurement surveys of the Mexican State, as seen below. All of them formed massive groups of migrants to different parts of the United States; however, the population of Tres Valles specifically settled in Kansas. In this way, an increasingly solid network of migration flows was built and, consequently, of relationships that can be interpreted as transnational migration.

In order to understand how Tres Valles was formed as a transnational community, the following are its characteristics and its process of transnational migratory emergence.

Tres Valles-Kansas: Emerging Migration Flow with Transnational Characteristics

The emerging migration flow that is analyzed in this article is that which has been formed from the mobility of people originating from the municipality of Tres Valles (Veracruz), who leave for the state of Kansas in the United States, among other destinations. It is called emergent because the migratory dynamics occurred from the 1990s onward, unlike the migration flows considered as traditional, which emerged at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. It is transnational because its members maintain relations that go beyond national borders.

The flow of migrants has been developed through interactions of communication, economics, and even political participation, using both official and unofficial channels. Through these exchanges, the people of Tres Valles have created social networks of solidarity among migrants between origin and destination, which has promoted commitments that maintain migration beyond merely economic incentives (Kearney, 1991; Rouse, 1992; Portes et al., 1999; Basch et al., 2005; Wimmer & Glick-Schiller, 2006; Ariza & Portes, 2007).

Tres Valles belongs to the region called Cuenca del Papaloapan. As the data provided by the National Council of Evaluation of the Policy of Social Development (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social [Coneval], 2015) indicates, this municipality of Veracruz is classified as having a high level of social deprivation. 60.4% of the population are in a state of poverty, while 15% of the total population of Tres Valles are classified as living in extreme poverty (see Table 1).

Table 1 National, state, and municipal percentages of people classified in different dimensions of poverty and social deprivation

| Scope | National/total population % | Veracruz | Tres Valles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 112 590 130 | 7 647 731 | 46 135 |

| Poverty | 46.3 | 58.4 | 60.4 |

| Extreme poverty | 11.4 | 19.3 | 15.0 |

| Moderate poverty | 34.9 | 39.2 | 45.4 |

| Vulnerable due to social deprivation | 28.8 | 24.1 | 27.4 |

| Vulnerable due to income | 5.7 | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| Not poor and not vulnerable | 19.3 | 13.3 | 7.8 |

| Education gap | 20.6 | 26.1 | 30.5 |

| Lack of access to health services | 31.8 | 36.9 | 41.9 |

| Lack of access to social security | 60.7 | 69.9 | 67.2 |

| Lack of quality and space in dwellings | 15.2 | 24.5 | 22.2 |

| Lack of basic services in dwellings | 23.0 | 40.4 | 48.7 |

| Lack of access to food | 24.9 | 26.5 | 24.1 |

| Population with at least one deficiency | 75.0 | 82.5 | 87.8 |

| Population with at least three deficiencies | 28.7 | 43.1 | 44.1 |

| Population with income below the welfare line | 52.0 | 62.6 | 64.8 |

| Population with income below the minimum welfare line | 19.4 | 28.3 | 24.2 |

Source: created by the author with data from Coneval (2015).

The data in Table 1 provide a picture of poverty conditions that are above the national and state average. The main deficiencies of the people of Tres Valles are the education gap, the lack of basic services in dwellings, and the lack of access to social security, the latter reflecting the precariousness of employment that emerged from the 1980s in the state of Veracruz. Furthermore, 64.8% of the population of Tres Valles has an income below the welfare line. In other words, all of these deficiencies and vulnerabilities have led Veracruz residents, including those of the population of Tres Valles, to seek better conditions in U.S. territory.

On the other hand, data from the National Population Council (Consejo Nacional de Población [Conapo], 2012) places Tres Valles as a medium-level municipality in terms of the degree of migration intensity. Regarding the municipality of Tres Valles, the data from Conapo in 2000 registered 1 361 homes with a member who was a migrant in the United States, representing 12.15% of a total of 11 206 (980 homes received remittances). For 2010, according to the Migration Intensity Index,5 Tres Valles was rated medium: of its 12 940 households counted, 5.9% (763 homes) received remittances, and 4.85% (621 homes) registered migrants in the United States in the previous five-year period. In terms of migration intensity, Tres Valles was ranked 44th out of 212 municipalities in the state of Veracruz (Conapo, 2012).

Source: created by the author with data from XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda 1990 (Inegi, 1990); XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000 (Inegi, 2000); Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010 (Inegi, 2010); Encuesta Intercensal 2015 (Inegi, 2015).

Figure 2 Tres Valles demographic behavior, by gender, 1990-2015

Migration in the municipality of Tres Valles in the period 2000-2010 was intense, and this was evident in the decrease in its population during these years, as shown in Figure 2. The migration was initially purely male, although later, women and entire families were included.

With an impoverished population and a desire to improve their quality of life, the population of Tres Valles became transnational migrants and gradually chose Kansas as a place of arrival and second location of community settlement.

The other location that is part of this new migration flow is the state of Kansas. This is one of the 50 states of the United States of America, located in the Midwest region of the country. The data provided by Migration Information Source on the situation of migrants in the state of Kansas indicate that the migrant population increased from 62 840 to 134 735 people between 1990 and 2000, representing a growth of 114.4%; between 2000 and 2011, immigrants in the state of Kansas increased to 198 767, with an increase of 47.5%. Thus, in 2011 the immigrant population in the state of Kansas represented 6.9% of the total population in the state, a significant increase from 5% in 2000 and 2.5% in 1990. By 2015, according to information obtained by the American Community Survey, the estimated population for the state was 2 892 987 inhabitants, of whom 11.17% are Hispanic (323 218 inhabitants), and among them, 9.4% are Mexican (271 112 inhabitants).

The poor population in the state of Kansas represents 13.18% (381 353 inhabitants) of the total population; of this total, 20.9% are Hispanic (79 775 inhabitants), and, among them, 17.6% are Mexican (67 023 inhabitants). In other words, Mexicans represent 84% of the total number of poor Hispanics in the state─one in every five Hispanics. Likewise, the American Community Survey in 2015 reported─only for 51 of 105 counties─that one out of every four Mexicans is in a condition of poverty.

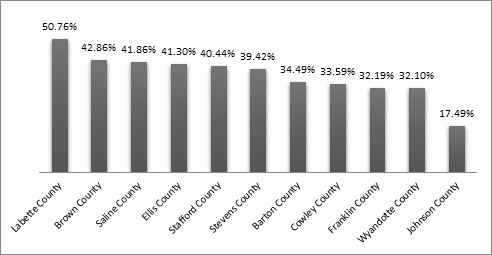

Source: created by the author with data from American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2015).

Figure 3 Main counties with the highest percentage of Mexicans living in poverty in the state of Kansas

Figure 3 shows the percentage distribution of the ten counties with the highest rate of poor Mexicans living in the state of Kansas. Furthermore, it also includes Johnson and Wyandotte counties, where most Tres Valles people live, and it was in those counties that the fieldwork was done.

On the subject of poverty, it should be noted that, like Mexico,6 the United States7 has its methodologies for measuring poverty, so both countries determine who is or is not in a situation of poverty. Thus, this analysis is not based on a one-dimensional comparison (income or expenditure) of poverty, but rather takes advantage of the convenience of subjective experiences regarding poverty, which at the same time acts as one of the driving forces behind the constant emigration of Mexicans to the United States, and the fact that, paradoxically, many Mexicans experience precarious conditions upon arrival in the neighboring country to the north or, in other cases, revise their narratives to note the change in perspective regarding the shortcomings, needs, or expectations of being a migrant and whether they consider themselves poor.

Theoretical Framework

Perception of Poverty in an Emerging Migration Flow

Poverty is conceptualized from different perspectives, but above all, it is understood as a condition in which individuals do not possess sufficient resources to satisfy their basic needs (Rowntree, 1901; Sen, 1992; Room, 1995),8 that is, to have a minimum standard of living. In order to understand the phenomenon more broadly, other variables have been added to the classic poverty measurements to complete a poverty measurement that addresses all types of deprivation, whether tangible or not, such as vulnerability, isolation, and lack of power (Chambers, 1983); or the satisfaction of basic needs (Chambers, 1983; Doyal & Gough, 1998). Likewise, in the last decades of the 20th century, poverty, as measured by the notion of capabilities, underwent a major upswing, drawing attention to conditions of deprivation and quality of life (Nussbaum & Sen, 2004; Desai, 2006).

However, Eric Hobsbawm (1968) states that “poverty is always defined according to the conventions of the society in which it occurs” (p. 398); from this, it can be said that there are both structural and individual factors that are related to the conceptualization of poverty. For the reason above, a generalized concept of poverty cannot be held without considering certain particularities of the places (one of both poles of a migration flow) and conditions (status, whether of migrants, or non-migrants dependent on remittances) in which every individual develops their perceptions.

Finally, Peter Townsend (1993) indicates that poverty should not only be understood based on a deficient distribution of resources but should also be considered concerning people whose resources “do not allow them to comply with the elaborate social demands and customs that have been placed upon the citizen of that society” (p. 36). It is in this sense that the “voice” of those facing the condition of poverty is of the utmost importance, especially in a subjective sense (González, 1986; Hagenaars & De Vos, 1988; Pradhan & Ravallion, 1997; Narayan, 2000; Székely, 2003). The perception of “feeling” oneself poor or not (Atkinson, 1974) is framed in the conditions in which the individual does not adhere to the activities of the community in which they live (Sen, 1983).

For this work, the perception of poverty is the consideration of each individual that includes the interpretation of their economic condition (income), in addition to considering social, cultural, and political aspects such as common beliefs, ways of life, ideals, and belonging, on the one hand, and, on the other, aspects that are related to the transnational in migration, such as exchanges, transnational life, and simultaneous identity. These are categories that emerged from the analysis of the narratives of the interviewees during the fieldwork. These aspects allow the subject to make a comparison with other individuals and determine whether or not they live in a state of poverty.

These types of self-perceptions reveal how well a subject fits into the society in which they live, for example, when the people from Tres Valles arrive in Kansas; the perceptions rooted in ideals, for example, what changes they perceive in poverty as a function of transnational migration relationships; the situation of bifocality, that is, how the people from Tres Valles who have the opportunity to travel continuously between Tres Valles and Kansas situate themselves in their narratives.

Transnationalism

One of the characteristics of the transnational migration flow between Tres Valles and Kansas is that migration went from being purely male to including women (see Figure 2) and entire families, which shows that the exchanges were more solidly interwoven since male migrants were no longer a source of economic resources for those who remained in Mexico, but rather the daily life of entire families moved from one place to another.

Symbolic content emerges in transnational migration. Some of the concepts that the transnational theory of migration provides are bifocality (Vertovec, 2004), simultaneous identities (Glick Schiller et al., 1992; García, 2012), multi-locality (Guarnizo & Smith, 1999), hybrid identity (Kearney & Nagengast, 1989), and community in movement (Besserer, 1999), which were used and observed in the analysis presented here.

Methodological Strategy

The methodological strategy of this research was developed in the following order. A review of concepts and theoretical discussions on the perception of poverty was carried out; from this, a semi-structured interview guide was designed9 with different categories. These categories were: perception of poverty, the effects of migration, transnational relations, comparisons between living in Kansas or Tres Valles, and the experience of migration dynamics as a motivation to face the condition of poverty.

The Kansas City metropolitan area was visited in 2016 (March to May),10 because of the considerable number of people from Tres Valles who arrived in this city (the fieldwork was done in two counties of the state, Johnson and Wyandotte, where most people from Tres Valles have settled). Key actors were contacted, such as the migrants who were the first to leave Tres Valles. Through these first migrants, links were established with other migrants. This dynamic made it possible to observe how support networks were formed and strengthened, and a type of discourse emerged that promoted this migration flow related to the reduction of poverty through salary and employment opportunities.

Work visits were made to the places where the people from Tres Valles were concentrated in Kansas (restaurants, construction companies, businesses belonging to people from Tres Valles). The city of Overland Park was visited, where there is a “neighborhood” called “Tres Vallitos”. Tres Vallitos has been a magnet for this migration flow since a good part of the immigrants have arrived there in their initial process of adaptation to their destination.

In the second phase of the fieldwork, the municipality of Tres Valles was visited.11 The same interview guide was used with people who had lived in Kansas and were returnees, as well as people who had never emigrated but had a direct relationship with a family member or friend in Kansas, including those who, because they have a U.S. resident status or visa (type B1/B2 tourism and business), can travel continuously from Tres Valles to Kansas.

As for the interviewees, those who are involved in the dynamics of migration, including those who have not migrated, are considered to be part of emerging migration flow. In other words, they correspond to what Levitt (2003) says about those who have not yet migrated,12 but who are an integral part of this international movement.

In both locations, Tres Valles and Kansas, 40 interviews were conducted. It should be noted that all the interviews in this article were conducted in 2016. Regarding the characteristics of the interviewees,13 as much diversity as possible was included: men, women, with and without migratory regularization in the United States, single and married, repatriated, and those who returned voluntarily to Mexico.

The interviews were analyzed from the consideration of the narratives created by the migratory dynamics in the emerging flow. The intention of looking for a set of narrative plots related to the perception of poverty between the place of origin and destination was supported by the idea conceived by Rorty (2002), who gives priority to the power of the description of the events and experiences of the individual, so that the individual, in relation to others, has a parameter of analysis and understanding of the social reality.

Finally, the narratives on poverty are analyzed based on the theory of the social imaginary that indicates the “organization” of society itself (imaginary social meanings) and defines what is considered relevant in the flows of information and what is meaningless (Castoriadis, 1986). The social imaginary allows us to interpret the way people think and act (Pintos, 1995; Falleti, 2006; Aliaga & Pintos, 2012), as well as to understand the establishment of institutions in society through the creation of imaginary meanings, which institute a world of norms, values, narratives, and language.

Discussion of Findings

What does Poverty Mean?

Of the various dimensions of the conceptualization of poverty, there is one that has taken on considerable importance in recent decades: subjective poverty. Contrary to objective measurements such as monetary expenditure and income, in the subjective dimension there is greater interest in the perceptions of people considered poor, although the perceptions of people who are not considered poor are also taken into consideration. The subjective aspect of poverty is linked to the satisfaction of needs; this provides valuable suggestions for understanding the micro-social characteristics that belong to individuals and that are not regularly reflected by quantitative studies. From the above, the interviewees were asked, initially, about their conception of poverty as a migrant in an environment different from that of their place of origin, in the understanding that in this case of analysis the migratory dynamic is fundamental in the discussion of the findings:

Poverty would be a lack of food, shelter. Obviously, without the monetary benefit, it is very difficult to acquire or supplement your basic needs. Here, poverty sometimes means not knowing how to speak English and not having the basics to give your family a more or less dignified life (Ismael, 23-years-old, has lived in Kansas for 13 years. He has been a beneficiary of the Dreamers program).

Well, many think that being poor is to live as a marginalized person, to live in what they call extreme poverty. Many who say, “Ah, I’m poor”, think that it means living on the streets and being filthy, but no, there are different types of poverty (Manuel, a 30-year-old single man who has lived in Kansas for 9 years).

In the perception of the emigrant, by observing another scenario and another possibility, they reconstruct meanings of a condition so common in their place of origin. This “alternative” vision facilitates a process of comparison that leads the emigrant to discuss, with greater self-criticism, the conditions of poverty in which they live or which they experienced at another time. The comparison is an exercise that the people of Tres Valles practice to a greater extent since the beginning of the migration flow, since previously they did not have a point of reference.

In this sense, bifocality, as understood by Vertovec (2004), is the result of the conveyance of experiences in the place of origin and destination in a migration flow. In this way, Tres Valles residents who are “potentially” migrants make a reckoning of what they experience in Tres Valles and the things that may be related to the condition of poverty in Kansas. Regarding the comparison of opportunities between being in Kansas as a migrant or in Tres Valles, the interviewees responded:

Going there really is like a dream, like an initiative in something you want to do. I have been told that, in that country, even though you are a migrant, you are given the opportunity to attain your goals. Well, that is the advantage of being an immigrant in Kansas. There are jobs and good salaries there. That is what my friends have told me, and it shows because when they come back, some can buy themselves a house or a plot of land, although not everyone comes back with good savings (Mundo, man, 27-years-old, lives in Tres Valles and has never emigrated to Kansas. He considers that he lives in poverty).

In the account of Mundo, one can see the way of life in terms of identifying the material conditions of life when in Tres Valles, while at the same time expressing his ideal if ever he has the option of emigrating to Kansas. This would support the discursive interpretation of some Tres Valles people when they state that life in the United States, despite the difficulties of leaving their country of origin, is much better in certain aspects than the life they can achieve in Tres Valles. In a sense, the following response contains similar details to the narrative of Mundo.

I have been told that the salaries are good, that people are freer to acquire goods somehow or other, and that they have more comfort in their lives. But there’s always some give and take, in Tres Valles you can be at ease because you are from here, there you cannot have this freedom, even if you have more money, you feel persecuted by the migration authorities. I think that shows the difference in how you feel here and there. In one place they have a lot, but with little freedom, and here, we have freedom, but we do not have as much access to material goods, it will always be like that (Antonio, a 28-year-old single man who lives in Tres Valles and has never migrated to Kansas. He works in agriculture).

When people who have never migrated and have no intention of doing so were asked how they imagine Kansas, they focus on very specific aspects: “there’s work there”, “it’s safer”, “they respect your rights”, “you make more money; therefore there is less poverty”, “it looks safer than here”. When a person from Tres Valles arrives in Kansas, they can adapt in such a way that the condition of poverty can be diminished by the fact of their “preconceptions” of the place where they intended to arrive (full of work opportunities, job security, the advantage of the value of the dollar over the peso, among others). Tres Valles represents the other side of the coin of this transnational scenario: “here there’s less work”, “it’s less safe”, “nobody respects the rights of a person”, “you earn less money, consequently there is poverty”, “there are opportunities, but they are very badly paid”.

In this case, the scenarios that migration has brought with it are of double contingency. In other words, when departure from Tres Valles first became an option to face conditions of poverty, the discourse acquired expressions of comparison of conditions and opportunities. Whoever is classed as poor, as long as they do not have a point of comparison, understands that condition as “natural” because it has “always” been so in that environment; subjective conflicts commence at the moment of seeing, experiencing or, at least, hearing about another way of life. The same applies to what Townsend (1993) observed as the deficient distribution of wealth.

Gabriela, who knows both sides of the coin─the experience of living in Kansas and Tres Valles─sees poverty as “not having enough to take home”. At the same time, she was asked about poverty in Kansas.

Well, I have known people in poverty, people who do not have enough money for what they call “los biles” [sic], which are the basic expenses. They go to places where the government or some agency helps them. Sometimes they need to go and ask for money to pay the rent, to pay for electricity and gas. Poverty does exist. Because often it is difficult for Latinos and undocumented people there to get a job (Gabriela, a 61-year-old woman. She lives six months in Kansas and six months in Tres Valles, and has permanent citizenship in the United States. She has been an emigrant since 2002).

These testimonies are related to what various authors have theorized about the subjective dimension of poverty. When talking about poverty in the measurement or understanding of poverty, it is necessary to consider the opinion of the experts, as well as to listen to the voice of the person regarding their economic situation together with what they consider wellbeing (Narayan, 2000; Székely, 2003).

The Effects of Transnational Migration and the Perception of Poverty

The estimate of the amount of income required to live varies according to the location and experience of each migrant, but always includes some form of comparison. Beyond the figures indicated by the institutions, for the people of Tres Valles, poverty has to do, indeed, with the availability of a certain amount of income to maintain a specific quality of life, which is obtained primarily through a salary. However, the people from Tres Valles state in their narratives that there are other aspects that the official measurements do not manage to indicate directly, such as leisure time, the time that heads of households can share with their families, or the perceived security of their neighborhoods. As will be seen below, both considerations of poverty and wellbeing have been disrupted since the migration to the north increased.

On the one hand, the people from Tres Valles managed to access better-paying jobs by migrating to Kansas, especially when compared to those they had in Mexico. Nevertheless, this wage evolution brought negative results, at least at the family level.

(…) because here, a day laborer or a person who lives from work in the fields, let us say they earn 100 pesos, 150 pesos a week, what can they buy? When a liter of milk costs at the very least 12 or 13 pesos, and that is the lowest price of milk. Imagine, a family with five or six members, how are they going to live on 100 pesos when they have to pay for water, electricity, and some people even rent because they have no place to live (Gabriela, a 61-year-old woman. She lives six months in Kansas and six months in Tres Valles, and has permanent citizenship in the United States. She has been an emigrant since 2002).

People who have experienced living in Kansas and have returned to Tres Valles have a particular way of seeing and, above all, comparing the income they earn as an immigrant or resident of Tres Valles. In other words, with this type of comparison, what becomes evident is that the social imaginary, through the dimension of ways of living, facilitates the interpretation of a condition such as poverty.

In Kansas, the times as I have been there, from what I have seen, there is a lot of work, people work a lot, but they have a certain amount of comfort. It is a quiet place where it is safe, where you can walk safely. But in our country, as we were saying, there is work, but it is poorly paid, people work a lot, but they earn little. People work to eat, to survive, and there are no comforts (Luna, 51-year-old woman. Married. She travels to Kansas at least once a year since 2010 to visit friends and family).

From the perspective of Luna, the only option to overcome the condition of poverty in which a good part of the population in Tres Valles finds itself is through obtaining jobs with better salaries. In fact, when she was able to contrast the conditions of how immigrants live in Kansas, her perspective changed, so her narrative began to be much more critical of the dominant reality in the municipality. Her narrative points to the comforts that people have in Kansas despite the housing conditions or the fact that migrants do unskilled jobs but have sufficient wages to support their families in dignified conditions.

Concerning this, the interviewees in Kansas were asked about the elements required to stop being poor, to which they responded:

Here in Kansas, at least to not feel poor you need to have a job with a minimum wage of $10 an hour, a car to be able to move around, and it is also a basic need to have a cell phone, oh, and I was thinking having a home to live in, because the rent is expensive, and with that, you can be more or less well off. If you have 100 dollars left over to send to your family in Tres Valles, it means that you are managing your money well (Manuel, single, works in gardening, arrived in Kansas in 2008).

In the narrative of the emigrants from Tres Valles, it can be seen that there is an exchange in the scale of articles or goods that one must have in order not to be poor. A car and a cell phone are two goods that in Tres Valles are not necessary, while in Kansas, they are considered “prime necessities” to be able to access a job. Tres Valles residents in Kansas also stated that these goods are necessary because there is no public transportation in the city, and only through cell phones can they keep in touch with employers and their networks of friends who can get information about jobs or other opportunities. However, in Tres Valles, the views of what it takes to not be in poverty are as follows:

It takes a lot of things in my mind. First, health, without that, you cannot do a job, especially if the person works in the fields. Second, education, at least high school. Third, a job in which you earn at least 5 000 pesos a month. A house of your own, and from time to time, you can take a vacation with your family. I was in Kansas, I can tell you that things are different, you earn more there, but you spend more, here you spend less, and the food is cheaper. Fortunately, I was able to build my own house, so I do not pay rent. What I am telling you is what it takes to consider that you’re not poor around here (Silvio. Man. Married. He lived in Kansas for ten years. He now lives in Tres Valles).

The narrative of Silvio is noteworthy because he is one of the members of the flow of migrants who have been in Kansas and, by the time of the interview, was living in Tres Valles. With this bifocal perspective (Vertovec, 2004), Silvio insists on transnational comparisons: on what is necessary to remain in Tres Valles, and also on what elements he previously did not consider (before he emigrated) but now does.

On the other hand, it seems evident that those who have migrated to Kansas adapt a new scale of needs that depends on the amount of the expenses necessary to live comfortably. Consequently, certain goods could be seen as luxuries in the place of origin, but in Kansas are perceived as basic needs:

It would be shelter, food, having a vehicle because it is more difficult to walk without a vehicle because it is not like in your own country. I remember─even though I came here when I was nine years old─I remember taking my bike, going to school, here you couldn’t do that (Ismael, 23-year-old man, has been living in Kansas for 13 years. He has been a beneficiary of the Dreamers program).

When I lived in Kansas, what I had was a good income, but I did not have much time to share with my family or friends, there was no quality time as they say. Now, here in Tres Valles, I have a lot of time, but the income isn’t enough, it seems that you can never have time and at the same time a good income, it seems that this cannot be achieved, you always have to be sacrificing something in order to live well (Noel, 27-year-old man. Married with two children. Currently lives in Tres Valles. He lived in Kansas for three years).

Time and income become “goods” that are interpreted to self-determine the poverty in which one lives. According to Noel, not having quality time is one of the ways of expressing dissatisfaction with certain needs, such as spending time with the family. Even though he had a sufficient and adequate income in Kansas, he did not have the quality time that his family or friends demanded of him.

Consumption becomes something that is adapted and is understood differently depending on which side of the border the people from Tres Valles are on. On the other hand, the expectation of a good quality of life and consumption is linked to migration and the possibility of receiving remittances from a migrant relative:

If I had had my son back in Kansas, I could still have my car, pay my bills, and be able to provide my son with everything he needs just by having a job. That is almost impossible here in Tres Valles. What I would most like to have is time, quality time, leisure time, and to be able to live comfortably with my family. Not having time makes me consider myself poor, and I know that it is going to be very difficult to get out of this situation (Gabriel, 25-year-old man. He lived in Kansas for almost four years as an undocumented immigrant and returned voluntarily to Tres Valles).

The type of consumer items in Kansas seems to determine the purchasing power of income that is earned. At the same time, there is a desire to migrate as a way to improve not only the level of consumption but also the conditions of the family. In Tres Valles, it is difficult for Gabriel to have a cell phone with a calling plan like in Kansas, much less rent an apartment or have his own car. Gabriel is waiting for the moment to be able to go back to Kansas, have a salary, and be able to give his wife and son a better quality of life, based on covering expenses and not only consuming the basics─which is what they think can be achieved in Tres Valles─, especially when he talks about his son and quality time, which is a subjective way of comparing the advantages of working less time with a better salary. Poverty, in this sense, is also interpreted from the perspective of free time.

In this sense, the needs vary according to the guidelines that make them up. Regarding this aspect, the following question was asked of the interviewees: what are the main needs that a person must satisfy to live peacefully in Kansas or Tres Valles? These were the answers obtained:

Well, it would be the basic needs of shelter, food, clothing, and nowadays trying to give the best to our children, within our means. As immigrants, it is a little more difficult, but if you aim to do so, then you can achieve it (Abel, 39-yeard-old, has lived in Kansas for 13 years).

I consider the three main ones to be education, health, and food (Patricia, a 56-year-old retired woman who lives in Tres Valles and has never emigrated and has no interest in doing so).

Among those interviewed who are migrants in Kansas, education is not a necessity, especially for those who have reached working age, that is, who were over 18 years old when they arrived in the United States. This difference is highlighted because, for respondents living in Tres Valles, education (some refer to this as attending school or obtaining a “degree” at the college or technical level) represents a necessity to overcome adverse economic conditions. In many cases, people have been able to address poverty with the help of some tools such as professional preparation.

Poverty often manifests itself and is perceived differently in either location. However, employment is seen as the starting point for addressing it or at least minimizing its consequences:

Here in Mexico, that is what bosses do: they take three, four, or five workers and say, “you know what, if you want, you can earn this much”, and they have you working your butt off all day. But it is difficult; for 100 or 200 pesos, they want to take everything out of you, they want to finish you off in a day. It is not worth it, honestly (Felipe, a 61-year-old man. He once tried to emigrate to Kansas but was unsuccessful).

Interviewees were also asked the following: do you feel that you have been excluded because of your Mexican immigrant status here in Kansas, and in what way?

Well yes, because the lack of documents limits one in many areas because if you wanted to start a company with all the necessary permits without fear of anything, it’s necessary to have your documents in order (Abel, 39-year-old man, has been living in Kansas since 2003).

Exclusion can be interpreted as a lack of decent employment, in the case of Felipe; and in the case of Abel, who lives in Kansas, it is due to “lack of documents”, which also translates into exclusion, as he does not have access to better-paying jobs. When the recording had finished, Abel told us that on some occasions he had to accept jobs with below-average salaries, for example, working as a dishwasher for seven dollars an hour, when they usually paid ten dollars an hour, but because he did not have documents the employer took advantage of his status.

Conclusions: the Effects of Emigration on the Perception of Poverty among the People of Tres Valles

As this study shows, the perception of poverty among the members of this transnational migration flow is marked by a symbolic construction that links the here and the there in relation to the migratory dynamics, their bifocality, ways of living, and common beliefs (Glick Schiller et al., 1992; Besserer, 1999, Vertovec, 2004).

The emerging migration flow from Tres Valles to Kansas grew significantly from the 1990s onward. In this first stage, emigration to Kansas was mostly male. From 2000 onward, women and entire families began to be integrated into the migration dynamic. This migration dynamic represented a massive outflow of people to Kansas so that networks between the place of origin and destination were strengthened, to enable migration to become transnational. Due to the financial crisis in the United States, from 2008 onward, the departure of people from Tres Valles was halted, and consequently, the forms of interpreting the “good life” of the migrant in Kansas changed toward narratives that questioned the benefits and opportunities of the “American dream”. The people from Tres Valles still value the importance of access to better jobs and wages, which they have found in Kansas, but their narrative also includes the importance they have begun to give to subjective elements such as the use of time, family union, and health, among other aspects whose absence leads them to believe that they are in conditions of poverty.

The perception of poverty is subordinated to the conditions that the individual experiences, beyond income or consumption, that is, when this condition is spoken of as a lived situation, the people from Tres Valles who have not emigrated explain poverty as a condition of deprivation due to the lack of work opportunities related to low wages, conditions that force them to emigrate. Likewise, individuals who have never migrated to Kansas consider that there is no possibility of finding poor people in the “North”. On the other hand, those who have left and come to Kansas, because of their own experience and observations, indicated that there is poverty in both places. However, poverty in Tres Valles is more difficult to bear (and eradicate) than in Kansas, where many find help from the government or religious communities (Catholic and Protestant churches).

Since the emerging migration flow that was analyzed is located in Veracruz─a state that suffered the dismantling of its peasant and industrial structure and, therefore, of jobs, starting in the 1980s─it is possible to conclude that the people of Tres Valles are subject to these changes. They conclude that poverty can be overcome through access to work and better salaries since it reflects the precarious jobs they have access to at the state level.

Finally, the dynamic presented in the emerging migration flow is transnational and offers the opportunity to observe the evolution and adaptation of concepts that have been relevant for the study of migration: border, interactions, communication, and exchanges, among others. These concepts are, in turn, perceived and interpreted by the members of this flow based on objective and subjective elements, in this case, the condition of poverty, from which the transnational narratives derive.

REFERENCES

Alarcón, R., Escala, L. & Odgers, O. (2014). Mudando el hogar al Norte. Trayectorias de integración de los inmigrantes mexicanos en Los Ángeles. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Albo, A. & Ordaz, J. (2011). La migración mexicana hacia Estados Unidos: Una breve radiografía (Documento de Trabajo, 11/05). BBVA Research. http://www.agenciabk.com/emigracion_mexicana.pdf [ Links ]

Aliaga, F. & Pintos, J. L. (2012). La investigación en torno a los imaginarios sociales. Un horizonte abierto a las posibilidades. RIPS. Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas, 11(2), 11-17. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4135361&orden=403169&info=link [ Links ]

Alkire, S. & Foster, J. (2007). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7-8), 476-487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.11.006 [ Links ]

Anguiano, M. E. (2005). Rumbo al norte: nuevos destinos de la emigración veracruzana. Migraciones Internacionales, 3(8), 82-110. https://migracionesinternacionales.colef.mx/index.php/migracionesinternacionales/article/view/1227 [ Links ]

Ariza, M. & Portes, A. (Coords.). (2007). El país transnacional: migración mexicana y cambio social a través de la frontera. UNAM-Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales. http://ru.iis.sociales.unam.mx/jspui/bitstream/IIS/4418/9/pais_transnacionalc.pdf [ Links ]

Atkinson, A. B. (1974). Poverty and income inequality in Britain. En D. Wedderburn (Ed.), Poverty, inequality, and class structure. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Baeninger, R., Machado Bógus, L., Bertino Moreira, J., Vedovato, L. R., Magalhães Fernandes, D., Rovery de Souza, M., Siqueira Baltar, C., Guimarães Peres, R., Chang Waldman, T. Aires Magalhães L. F. (Orgs.). (2018). Migrações sul-sul- (2ª ed.). Universidade Estadual de Campinas https://oestrangeirodotorg.files.wordpress.com/2018/04/livro-migracoes-sul-sul.pdf [ Links ]

Basch, L., Glick Schiller, N. G. & Szanton Blanc, C. S. (2005). Nations unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation-states. Routledge. [ Links ]

BBVA. (2015). Situación migración México. Análisis Económico. BBVA Research México. https://www.bbvaresearch.com/publicaciones/situacion-migracion-mexico-primer-semestre-2015/ [ Links ]

Besserer, F. (1999). Estudios transnacionales y ciudadanía transnacional. En G. Mummert (Coord), Fronteras fragmentadas (pp. 215-238). Colegio de Michoacán-CIDEM. https://sic.cultura.gob.mx/documentos/1213.pdf [ Links ]

Binford, L. (2003). Migrant remittances and (under) development in Mexico. Critique of Anthropology, 23(3), 305-336. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0308275X030233004 [ Links ]

Castles, S., De Haas, H. & Miller, M. (2014). The age of migration international population movements in the modern world (5a. Ed.). The Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Castoriadis, C. (1986). La institución imaginaria de la sociedad. Tusquets Editores. [ Links ]

Chambers, R. (1983). Rural development: Putting the last first. Longman. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (Coneval). (2015). Índice de rezago social 2015 a nivel nacional, estatal y municipal. https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/IRS/Paginas/Indice_Rezago_Social_2015.aspx [ Links ]

______ (2019, junio). Metodología para la medición multidimensional de la pobreza en México (3ª. ed.). Coneval. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población y Vivienda (Conapo). (2012). Intensidad migratoria a nivel estatal y municipal. En Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos 2010 (pp. 33-44). http://www.omi.gob.mx/es/OMI/Indices_de_intensidad_migratoria_Mexico-Estados_Unidos_2010 [ Links ]

Delgado, R., (2013, 1 de febrero). The migration and labour question today: New imperialism, unequal development and forced migration. Monthly Review, 64(9), 25-38. https://monthlyreview.org/2013/02/01/the-migration-and-labor-question-today-imperialism-unequal-development-and-forced-migration/ [ Links ]

Desai, M., (2006). The route of all evil: the political economy of Ezra Pound. Faber and Faber. [ Links ]

Doyal, L. & Gough, I. (1998). A theory of human need. McMillan. [ Links ]

Durand, J. & Massey, D. (2019). Evolution of the Mexico-US migration system: Insights from the Mexican migration project. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 684(1), 21-42. [ Links ]

Durand, J., Massey, D. & Parrado, E. (1999). The new era of Mexican migration to the United States. Journal of American History, 86(2), 518-36. http://archive.oah.org/special-issues/mexico/jdurand.html [ Links ]

El Colef, Unidad de Política Migratoria, Conapo, Segob, SRE, STPS, Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación, Sedesol. (2002-2017). Encuesta sobre Migración en la Frontera Norte de México. Informe Anual de Resultados (varios años 2002-2017). https://www.colef.mx/emif/informes_publicaciones.html [ Links ]

Facchini, G., Frattini, T. & Mayda, A. M. (2015). International migration. En J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (2a. ed., pp. 511-518). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.31125-4 [ Links ]

Falleti, V. (2006). Los problemas de la construcción del conocimiento en las Ciencias Sociales. Una mirada crítica sobre las nociones clásicas el tipo ideal y la representación. Universitas Humanística, (62), 71-89. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=79106204 [ Links ]

García, N. (2012). Culturas híbridas. Debolsillo. [ Links ]

Garrido, C. (2010). El proceso migratorio veracruzano: aportes teóricos-metodológicos para su estudio e intervención. El caso del campo cañero (Biblioteca digital de Humanidades, Resultados de investigación, 6). Universidad Veracruzana. https://www.uv.mx/bdh/files/2012/10/proceso-migratorio-veracruz.pdf [ Links ]

Glick Schiller, N., Basch, L. & Blanc-Szanton, C. (1992). Transnationalism: A new analytic framework for understanding migration. A new analytic franework. Annals New York Academy of Sciences, 645(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb33484.x [ Links ]

González, M. (1986). Los recursos de la pobreza: Familias de bajos ingresos de Guadalajara. El Colegio de Jalisco/CIESAS/SPP. [ Links ]

Guarnizo, L. E. & Smith, M. P. (1999). Las localizaciones del transnacionalismo. En G. Mummert (Coord.), Fronteras fragmentadas (pp. 87-112). El Colegio de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Hagenaars, A. & De Vos, K. (1988). The definition and measurement of poverty. The Journal of Human Resources, 23(2), 211-221. [ Links ]

Hobsbawm, E. J. (1968). Poverty. En D. L. Sills (Ed.), International Encyclopedy of the Social Sciences. Macmillan. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). (1990). XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda. Inegi. [ Links ]

______ (2000).XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda. Inegi. [ Links ]

______ (2010). Censo General de Población y Vivienda. Inegi. [ Links ]

______ (2015). Encuesta Intercensal. Inegi. [ Links ]

Kearney, M. (1991). Borders and boundaries of state and self at the end of empire. Journal of Historical Sociology, 4(1), 52-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.1991.tb00116 [ Links ]

Kearney, M. & Nagengast, C. (1989). Anthropological perspectives on transnational communities in rural California (Documento de trabajo, Working Group on Farm Labor and Rural Poverty, 3). California Institute for Rural Studies. [ Links ]

Levitt, P. (2003). The transnational villager. University of California Press. [ Links ]

Massey, D. (2015). A missing element in migration theories. Migration Letters, 12(3), 279-299. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4933523/pdf/nihms769053.pdf [ Links ]

Massey, D. S., Alarcón, R., Durand, J. & González, H. (1987). Return to Aztlan: the social process of international migration from Western Mexico. University of California Press. [ Links ]

Narayan, D. (2000). La voz de los pobres ¿hay alguien que nos escuche? Mundi-prensa. [ Links ]

Nava, M. (2012). Migración internacional y cafeticultura en Veracruz, México. Migraciones Internacionales, 6(3), 139-171. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, M. & Sen, A. (Comps.). (2004). La calidad de vida. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Ortiz, J. & Ríos, H. (2013). La pobreza en México, un análisis con enfoque multidimensional. Análisis Económico, 28(69), 189-218. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/413/41331033010.pdf [ Links ]

Passel, J. & Cohn, D. (2008, 2 de octubre). Trends in unauthorized immigration: undocumented inflow now trails legal inflow. Pew Hispanic Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2008/10/02/trends-in-unauthorized-immigration/ [ Links ]

Pérez, M. (2012). “Nuevos” orígenes y “nuevos” destinos de la migración México-Estados Unidos: El caso del centro de Veracruz. Espiral, Estudios sobre Estado y Sociedad, 19(54), 195-232. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266856781_Nuevos_origenes_ya_nuevos_destinos_de_la_migracion_Mexico-Estados_Unidos_el_caso_del_centro_de_Veracruz [ Links ]

Phillips, J. & Massey, D. (1999). The new labor market: Immigrants and wages after IRCA. Demography, 36, 233-246. [ Links ]

Pintos, J. (1995). Los imaginarios sociales. La nueva construcción de la realidad social. Sal Terrae. [ Links ]

Portes, A., Guarnizo, L. & Landolt, P. (1999). The study of transnationalism: pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 217-237. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/200820331_The_Study_of_Transnationalism_Pitfalls_and_Promise_of_An_Emergent_Research_Field [ Links ]

Pradhan, M. & Ravallion, M. (1997). Measuring poverty using qualitative perceptions of welfare. Policy Research Working Paper Series, (2011), 1-42. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/218901468775832719/pdf/multi-page.pdf [ Links ]

Room, G. (1995). Poverty and social exclusion: The new European agenda for policy and research. En G. Room (Ed.), Beyond the threshold. The measurement and analysis of social exclusion (pp. 1-9). The Policy Press. [ Links ]

Rorty, R. (2002). Filosofía y futuro. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Rouse, R., (1992). Making sense of settlement: class transformation, cultural struggle, and transnationalism among Mexican migrants in the United States. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 645(1), 25-52. [ Links ]

Rowntree, B. S. (1901). Poverty: A study of town life. Macmillan. [ Links ]

Sánchez Carballo, A., Ruíz, J. & Barrera, M. Á. (2020). La transformación del concepto de pobreza. Un desafío para las ciencias sociales. Intersticios Sociales, 10(19), 39-65. http://www.intersticiossociales.com/index.php/is/article/view/255/pdf [ Links ]

Semega, J., Kollar, M., Creamer, J. & Mohanty, A. (2019). U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2019/demo/p60-266.pdf [ Links ]

Sen, A. (1983). Poor, relatively speaking. Oxford Economic Papers, 35(2), 153-169. [ Links ]

______ (1992). Sobre conceptos y medidas de pobreza. Comercio Exterior, 42(4), 39-58. [ Links ]

Székely, P. (2003). Lo que dicen los pobres. (Cuadernos de desarrollo humano, núm. 13). Sedesol. [ Links ]

Townsend, P. (1993). The international analysis of poverty [1073]. Harvester y Wheatsheaf. [ Links ]

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey. (2015). Annual Social and Economic Supplements. [ Links ]

Vertovec, S. (2004). Cheap calls: the social glue of migrant transnationalism. Global Networks, 4(2), 219-224. [ Links ]

Wimmer, A. & Glick-Schiller, N. (2006). Methodological nationalism, the social sciences and the study of migration: An essay in historical epistemology. International Migration Review, 37(3), 576-610. [ Links ]

Zurita, J., Martínez, J. & Rodríguez, F. (2009). La crisis financiera y económica del 2008. Origen y consecuencias en los Estados Unidos y México. El Cotidiano, (157), 17-27. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/ElCotidiano/2009/no157/2.pdf [ Links ]

1 The authors point out that the new era of migrations is from the late 1990s onwards. Other authors, such as Durand and Massey (2019), differ in terms of their names, but coincide in terms of their temporal location, at least in the case of Mexico and the United States.

2 U.S. poverty methodology. Individuals are classified as being below the poverty line using a poverty index adopted by the Federal Interagency Committee in 1969 and slightly modified in 1981.

3 The American Community Survey (ACS) is part of the Census program and through this survey the need for a long-format census questionnaire is eliminated. ACS provides comprehensive information on social, economic, and housing issues.

4 Between 1985 and 1990, the people of Veracruz went mainly to the State of Mexico, Tamaulipas, Mexico City, Puebla, and Oaxaca. In the 1995-2000 period, the main destinations of Veracruz residents were, in order of importance, Tamaulipas, Chihuahua, Mexico City, and Puebla in Mexico, which together accounted for 56.4% of all migrants. The increase toward the year 2000 in the participation of the states on the northern border of Mexico (Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas) as destinations for Veracruz migrants is noteworthy (Anguiano, 2005).

5 The indicators of migration intensity are: 1) Households receiving remittances (income from abroad). 2) Dwellings with migrants to the United States during the five-year period 2005-2010 who were staying in that country at the time of the census (migrants). 3) Dwellings with migrants to the United States during the 2005-2010 period who returned to the country during the same period (circular migrants) and who at the date of the census were residing in Mexico. 4) Dwellings with migrants who resided in the United States in 2005 and returned to live in Mexico before the 2010 census (return migrants) (Conapo, 2012).

6 Since 2006, Mexico has been measuring poverty using a multidimensional methodology (Alkire & Foster, 2007). In Mexico, someone is considered multi-dimensionally poor when their income is below the value of the welfare line and they suffer at least one social deficiency. The social deficiencies are: education gap, lack of access to social security, lack of basic services in dwellings, lack of access to health services, lack of quality and space in dwellings, lack of access to food (to expand the discussion on the issue of multidimensional measurement of poverty in Mexico see the work of Coneval (2019) and to a lesser extent that of Ortiz and Rios (2013).

7 According to the Boreau Census in the United States, in 2010 there were an estimated 46 million people living in poverty. For a family of four members to be considered below the poverty line, it should have an annual income of less than $23 050 (2012 estimate), and by 2016 the same family should have a salary above $24 300 per year so as not to be considered poor; in the same year it was counted that 40.6 million people “lived in the poverty zone” (Semega, Kollar, Creamer & Mohanty, 2019). This official measure of minimum income (poverty line) must be sufficient for the members of a family of four to cover their basic needs and thus ensure their adequate inclusion in society.

8 For more information on how the conceptualization of poverty has evolved, see Sánchez Carballo, Ruíz and Barrera (2020).

9 The thematic script of the interview is the following: a) Sociodemographic characteristics of the interviewees; b) poverty; c) subjective poverty; d) objective poverty; and, e) transnational relations. A thematic section was added to fit the characteristics of the interviewees, for example, if they were an emigrant returning to Tres Valles, or if they were an individual who had never emigrated.

10 In previous years (2010, 2012, 2014), visits had already been made to the Kansas City metropolitan area, where observations were made of the arrival of people of Mexican origin and from Tres Valles due to the wide range of jobs on offer.

11 Unlike other ethnographic works on transnational migration between Mexico and the United States, this one began in Kansas and not in Mexico, since the principal researcher visited his relatives several times before beginning the investigation, learned about the number of Tres Valles residents and, thus, on a trip to Kansas he took the opportunity to begin with the interviews and observations, and then replicate the process in Tres Valles.

12 There are also individuals whose lives are anchored in one place of origin or destination, who move infrequently, but whose lives are wholly bound up with resources, contacts, and people who are far away. There are others who do not move but live within contexts that have been transnationalized (Levitt, 2003, p. 179).

Received: November 20, 2019; Accepted: June 16, 2020

texto en

texto en